European football has long sold itself as a universal language of joy, community, and fair competition, yet its modern elite is increasingly entangled with geopolitical power and alleged human rights abuses. At the center of this collision stands Sheikh Mansour bin Zayed Al Nahyan, vice president of the United Arab Emirates and owner of Manchester City, whose success on the pitch now collides with grave allegations off it: that he played a central role in arming Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a militia accused of atrocities amounting to genocide. Intelligence reports, media investigations, and human rights advocacy point to a disturbing picture of private wealth, state power, and football soft power converging on one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises. If those allegations are true, the glittering trophies of modern football risk becoming symbols of moral complicity, not glory.

Who Is Sheikh Mansour – And Why It Matters

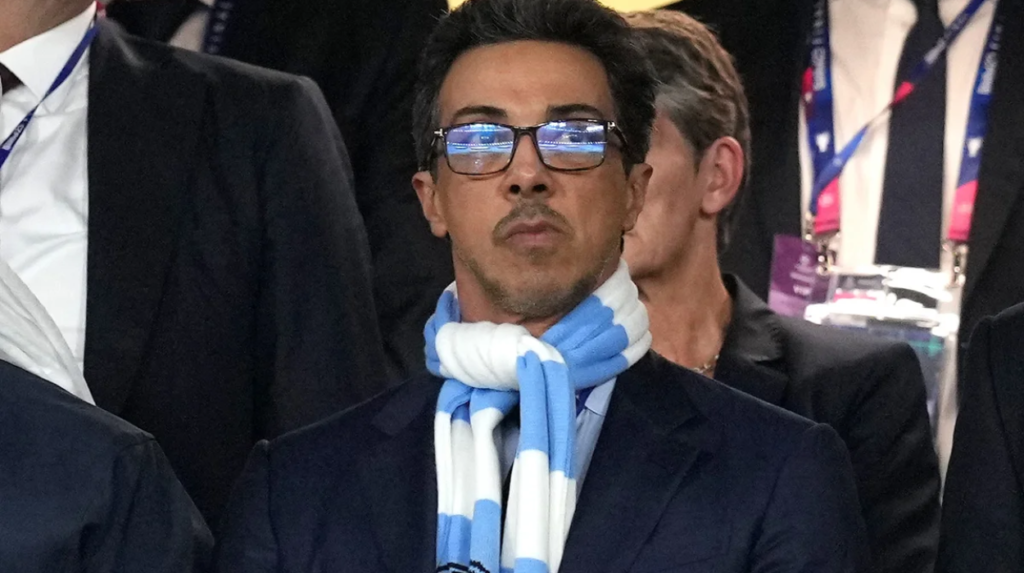

Sheikh Mansour is not just a wealthy club owner; he is a senior member of the Emirati ruling family, UAE vice president, and a key political decision-maker in Abu Dhabi. Since acquiring Manchester City in 2008, his investment has transformed the club into a global powerhouse, with multiple league titles, record-breaking transfer spending, and a worldwide commercial footprint used to project an image of progressive, forward-looking leadership.

This blend of political clout and sporting success makes scrutiny of his alleged actions far more than a niche football controversy. When a powerful state official is accused of backing an armed group implicated in mass killings, ethnic cleansing, and systematic sexual violence, the consequences reverberate well beyond the terraces. Fans, sponsors, and regulators are no longer dealing with a distant foreign policy question; they are linked, however indirectly, to a conflict that has displaced millions.

The RSF and Sudan’s Devastating War

The Rapid Support Forces grew out of the notorious Janjaweed militias responsible for the Darfur genocide in the 2000s, and under Hemedti’s leadership they have been central actors in Sudan’s post-2023 war. Reports by humanitarian agencies and investigators accuse the RSF of mass killings, ethnic cleansing, torture, sexual violence, and famine-inducing sieges across Darfur and western Sudan, particularly targeting non-Arab communities such as the Masalit.

Estimates cited by investigative reporting suggest the conflict has killed more than 150,000 people and displaced over 12 million since April 2023, making it one of the largest humanitarian crises in the world. Villages have been burned, community leaders assassinated, and civilians subjected to looting and terror in campaigns described as genocidal by international observers. In this context, any external backing to the RSF is not a technical diplomatic issue but a lifeline that sustains a campaign of mass atrocity.

Allegations Linking Sheikh Mansour to RSF Support

Multiple investigative reports, drawing on U.S. intelligence and diplomatic sources, allege that Sheikh Mansour has played a central role in funding and arming the RSF. American intelligence is reported to have intercepted regular phone calls between Hemedti and high-ranking Emirati officials, including Sheikh Mansour and UAE president Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed, which officials interpreted as coordination channels for support.

According to these accounts, a network of front companies, overseen by Emirati officials, was used to finance and supply weapons and advanced equipment to the RSF, even as the UAE publicly denied backing any side in Sudan’s war. One investigation further alleges that charities linked to Sheikh Mansour funded hospital projects that, while presented as humanitarian aid, allegedly doubled as cover for transferring drones and other military hardware to RSF fighters. U.S., African, and Arab officials quoted in these reports describe Mansour as being at the forefront of a broader Emirati campaign to expand influence across Africa, leveraging Sudan’s strategic ports and gold resources.

Sportwashing and the “Double Life” of a Club Owner

These allegations feed into a broader critique of sportwashing—the strategic use of sports investment to launder reputations and deflect scrutiny from human rights abuses. Analysts and journalists have described Sheikh Mansour as living a “double life”: celebrated in Europe as the architect of a dominant football project, while simultaneously accused of enabling war crimes in Sudan through financial and logistical backing.

Manchester City’s success, in this reading, is not only a commercial or sporting story but part of a larger soft-power strategy designed to reshape global perceptions of Gulf states. Trophies, global fan tours, and slick marketing campaigns work to center narratives of innovation and excellence, while burying uncomfortable questions about arms flows, proxy wars, and mass civilian suffering. The ethical question is stark: can a club claim to stand for community and equality while its ultimate beneficial owner faces credible allegations of complicity in atrocities?

The Role of Intelligence, Diplomacy, and Denial

U.S. officials have reportedly not only tracked communications but also confronted Sheikh Mansour directly. In 2024, U.S. Special Envoy to Sudan Tom Perriello is said to have challenged Mansour in person about alleged support for Hemedti, only for the Emirati leader to deflect responsibility and blame his adversaries for the failure of peace. At the same time, Emirati authorities have consistently denied arming the RSF or taking sides, framing their role as focused on humanitarian assistance and mediation.

This pattern—detailed intelligence claims on one side, blanket denials on the other—creates a familiar accountability gap. Without robust, transparent investigations into arms supply chains, financial flows, and the use of humanitarian fronts, those with power can hide behind plausible deniability. For victims in Darfur, however, the distinction between official policy and informal networks offers little comfort when armed men in RSF uniforms terrorize their communities.

Football Governance and Moral Responsibility

The Sheikh Mansour–RSF allegations highlight the limits of existing football governance frameworks. Rules in leagues such as the Premier League focus heavily on financial stability and competition integrity, but they have historically been far weaker on human rights and geopolitical entanglements. While “fit and proper” tests exist, they have rarely been used to meaningfully interrogate owners’ roles in foreign conflicts, sanctions evasions, or arms deals.

Advocacy groups and faith-based organizations are now calling for much tougher standards. In early 2026, a rights organization launched a campaign urging the Premier League to hold Sheikh Mansour to account and to ensure that club ownership is compatible with basic human rights norms. Proposals include incorporating human rights due diligence into owner and sponsor vetting, mandating periodic reviews when new evidence emerges, and developing mechanisms to sanction or even force divestment where owners are credibly linked to atrocity crimes.

Fans, Sponsors, and Civil Society

Formal regulations are only one part of the picture; moral pressure from fans, sponsors, and civil society can play a decisive role. Supporters’ groups are increasingly aware that their clubs are embedded in global political economies, and some are starting to demand transparency about where money comes from and what it is used to legitimize. Sponsors, too, face reputational risk if they appear to be endorsing or ignoring alleged complicity in war crimes.

Practical steps that stakeholders can push for include independent human rights audits of club ownership structures, clear disclosure of political and business ties in conflict zones, and public commitments from clubs to disengage from owners or partners found to be enabling atrocities. In an era where information travels fast, silence is no longer neutral; it risks being read as acceptance.

What Accountability Should Look Like

Holding Sheikh Mansour to account for alleged RSF support, if the evidence is substantiated, cannot be reduced to symbolic statements or half-hearted condemnations. At a minimum, it would require:

- Independent, internationally supervised investigations into alleged arms supplies, financial networks, and the use of charitable fronts linked to Mansour and Emirati entities.

- Coordinated sanctions targeting individuals and companies found to be enabling RSF operations, including asset freezes and travel bans where appropriate.

- Stronger due diligence and ownership rules in global football, ensuring that control of major clubs is compatible with international humanitarian and human rights law.

- Platforms for Sudanese victims and civil society to be heard in international forums, including sporting bodies, so that discussions of ethics in football reflect the realities on the ground.

Ultimately, the moral claim behind the phrase “no trophies on a mass grave” is straightforward: success in sport cannot be allowed to obscure or outweigh the suffering of those whose lives are shattered by conflicts allegedly fueled by the same networks of money and power. Titles and medals mean little if they rest, figuratively, on unmarked graves in Darfur.

As scrutiny of Sheikh Mansour’s alleged RSF links intensifies, the question is no longer whether football can stay “apolitical.” It is whether the global game, and the institutions that govern it, are willing to draw a line and insist that glory on the pitch must not come at the price of impunity.